Wiki Education is hosting webinars all of October to celebrate Wikidata’s 10th birthday. Below is a summary of our third event. Watch the webinar in full on Youtube. And access the recordings or recaps of other events here.

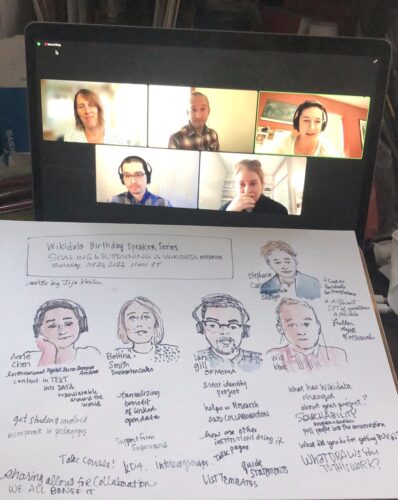

So far, we’ve covered the state of Wikidata and cultural heritage 10 years in and what you need to know to kickstart a Wikidata Initiative of your own. Last week, Will Kent brought additional experts together to reflect on scaling and sustaining Wikidata work within cultural institutions. Dr. Anne Chen, an art historian and archaeologist, joined us from the International (Digital) Dura-Europos Archive. Ian Gill is a Collections Information Systems Specialist at SFMOMA. Dr. Stephanie Caruso is a Giorgi Family Foundation Curatorial Fellow at the Art Institute of Chicago. Previously, she was a Postdoctoral Fellow in Byzantine Art/Archaeology at the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, where she worked with Bettina Smith, the current Manager of Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives. All four speakers completed a course through our Wikidata Institute at some point in the last three years, and we’ve loved watching their Wikidata Initiatives grow.

What does Wikidata allow that makes it unique from other platforms?

For Anne, Wikidata provides an opportunity to collaborate across continents and languages in a way she and her archaeological colleagues have never been able to do. She can draw together disparate artifacts and rebuild archaeological contexts virtually. And because Wikidata’s interface is set up for translation into many different languages, Anne and her team can invite their global colleagues to interact with their records, some of whom will have access to these records in their native language for the very first time. “Because of the democratic nature of Wikidata, we can pull additional people from all over the world into the conversation about linked open data at a relatively early stage.”

For Bettina, Wikidata is the place where Dunbarton Oaks’ collections can compare and contrast similar collections around the world. “That kind of aggregated search has been tantalizingly promised by linked open data for so many years,” said Bettina. “Wikidata is the first real manifestation of it.”

New research is possible from there, which is what Stephanie is particularly excited about. “With Wikidata you can work with much broader data in one consolidated place,” she said. “The questions you can ask of the material wouldn’t be possible if you had to go to each archive. That would be way too much work and too slow going.” When she and Bettina began cataloging collections of Syrian origin, they noticed that item names varied across different languages. Traditional repositories might ask to privilege one language over another. Not Wikidata. “Having a QID that is translatable between all these issues makes it possible to get a fuller depth of research.” And to that, Anne added: For how many generations have researchers been reinventing the same research? If someone can point to a Q number and no one has to do that work again, imagine! It’s easier to build on each other’s research if we don’t have to reinvent the wheel.”

At SFMOMA, Ian populates Wikidata records based on their permanent collection as part of the Artist Identities Project. Wikidata helps him represent artist information more ethically, generating metrics about who his institution exhibits and acquires each year, potentially informing the institutions’ future decisions. “A lot of museums are trying to do this work, and Wikidata is the central repository for it,” Ian said.

And it’s not just museums who are interested in improving linked open data. “I noticed there were Wikidata users that were enhancing our records, saying ‘oh this exhibition actually went to this other venue too.’ I could then add that information to our records. It’s cool to interact with others with the same goals.” It goes both ways. When institutions make improvements to Wikidata, that information has the potential to start a ripple effect. And in return, the institution benefits from access to a more complete repository. “The idea that content generated by amazing editors within the Wikidata community could be reabsorbed into a collection database and used for collection ends in the future is really exciting,” Anne added.

Editing Wikidata is also personally satisfying. Seeing your work out there with immediate effects is metadata’s version of instant gratification! “And it challenges the paradigm that your work has to go through and be checked by traditional levels of authority,” Will chimed in. “I forget sometimes that doing something for the first time, having attained this new skill, is something tangible, compelling, and addictive,” Anne added. “It’s a rush!” Bettina added with a smile.

How did they convince others at their institution to support them?

Most of us are new to editing, and even as we learn, Wikidata evolves. So how do you convey the opportunities it presents to your institution if it’s not a static platform and the possibilities are limitless? For Anne, learning enough of the basics to convey the value of a larger project was huge. “As an art historian and archaeologist, I went into the linked open data sphere feeling uncomfortable in my technical knowledge,” she said. “So I had to start at the beginning and develop content in Wikidata that I could use to demonstrate the promise. Ultimately the thing that got traction was not just talking about abstract ideas, but pointing to a case study. From there, I can talk about all the things I haven’t done yet and how this could be better if we all contributed to it and if we had buy-in from the institution to go full scale.” And once she and her team had a case study, they were able to apply for larger scale funding from the National Endowment of the Humanities–which they received!

Although Wikidata is a strategic fit for cultural institutions, many are hesitant about participating in an open platform where anyone can change anything. Stephanie had some ideas for calming nerves: “I tell them, ‘You already did a good job creating a stable URL for each object in the collection. If someone clicks on it through Wikidata, they will go to your website. There’s a unique property for a Met ID, something that links back to the Met’s site and the owners’ explanation of the object. That can reassure people that regardless of what’s happening on Wikidata, you’re not changing the authority of the institution.”

Presenting a “handbrake option” can also be reassuring. “Anything on Wikidata that is erroneous or disputed can be reverted,” Anne shared. “I’ve also found it useful to talk about the history of the edits that have been made to a particular object on Wikidata. Thinking from an archival perspective, the idea that there’s a record that there was a dispute about an object is an important facet for the next generation and for thinking about how we can more responsibly engage with multiple perspectives with the content we’re managing.” “It’s also worth making the point that if you don’t do it, someone else could,” Bettina added. “And they might not do it the way you would do it.”

What are the key elements for sustaining a project?

According to our speakers, the main elements for success are some combination of the following: Passion. Supervisor support for your time. Other colleagues’ help. Funding opportunities are also nice. And above all else, expertise and continual learning.

“The Wikidata Institute is probably the best possible resource,” Bettina shared. “There’s also things like LD4, the Wikidata interest group that meets every other week. And I’m a member of ARLIS, the Art Library Society of North America, and they have a Wikidata interest group that meets once a month. Those are useful ways to find out about tools and things that I would not otherwise have known about.” “Going through lists of tools that people have developed is also cool. That’s how I found QuickStatements!” Ian added. “I’ll also put in a plug for discussion pages and the Wikidata telegram channel,” Anne said. “As a new user I was a little intimidated about revealing my ignorance on certain issues or how to do certain things. But at Will’s encouragement, and as part of the course, we got to realize that everyone is learning something and the community is helping each other grow.”

How do they see Wikidata influencing their field in the next 5 or 10 years?

Anne sees promise in the multilingual collaborative nature of Wikidata and the effect that it could have for equity in her field at large. “I’m doing work that deals with cultural heritage material from Syria and I would love to partner with other institutions and offer Wikidata trainings. The payoff of that could be huge. For a project like mine, we could get more diverse perspectives looking at the content that we’re creating.”

Ian pointed out that there’s a lot more internal work to be done within cultural institutions to make things public. “I expect wider adoption of Wikidata in five years for sure. In terms of the Artist Identities Project, a lot of other museums are working on that and it has come up in meetings where people say, ‘What if there were a central repository we could pull from?’ And I get to say, ‘That exists! It’s Wikidata!’”

“Innately as a librarian, archivist, and reformed cataloguer, Wikidata just makes sense,” Bettina added. “I didn’t know it existed before two years ago and now I’m presenting on it! I’m seeing that rapid increase in interest in a lot of my library colleagues and other institutions and I think it’s just gonna grow exponentially from here. If there are any cataloguers in the audience, you can do it—I promise!”

Check out Ian’s project here, Bettina and Stephanie’s here, and Anne’s here and here.

If you’re the kind of learner who seeks community and guidance on your journey, the Wikidata Institute has three upcoming training courses starting in November, January, and March.

Great article, I think after reading a article also start using Wikidata. Thank you for providing such a excellent platform…