What’s the connection between explosives, major depressive disorder, and chest pain? I wouldn’t have known until I reviewed some student work from last semester.

If you’ve taken an advanced cell biology class, you may have heard of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cyclic AMP), a molecule that’s related to ATP (the “energy currency” that mitochondria turn sugars into) and adenine (one of the bases is DNA), but you probably haven’t heard of its less well-known cousin, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (just cyclic GMP among friends).

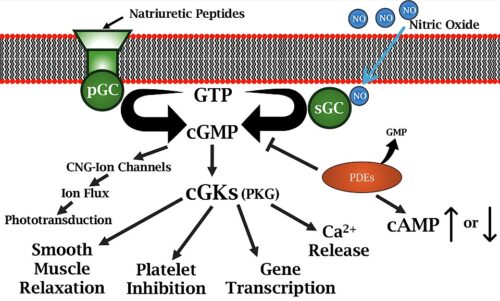

Much like cyclic AMP, cyclic GMP is what’s called a “second messenger” in cells. First messengers include molecules that carry messages around the body, from the organ where they’re produced to the cells where they actually have an effect. These include things like hormones.

While these “first messenger” molecules can travel around the body, most can’t get into cells. (Cells protect themselves by being very picky about the kinds of molecules they allow in.) Instead of entering the cells, these molecules attach to specific receptors on the cell surface, triggering the release of the second message – for example, cyclic GMP.

While some small molecules like nitric oxide are able to enter the cell, they still depend on second messengers like cyclic GMP to cause things to happen inside the cells.

Once activated, second messengers can set various processes in motion. Cyclic GMP, for example, can switch protein kinases on. Protein kinases are proteins that cut specific bits off other enzymes, which can either make those enzymes active (think about it like pulling the pin on a fire extinguisher) or inactive (like cutting the cord off an electric appliance).

While cyclic GMP was discovered only two years after cyclic AMP, research into cyclic GMP was largely overshadowed by Earl Wilbur Sutherland’s work on cyclic AMP, which won him a Nobel Prize in 1971. It’s hard to compete with that kind of publicity, but cyclic GMP had its own moment in the sun when Robert Furchgott, Louis Ignarro, and Ferid Murad were awarded the 1998 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine based on their work with cyclic GMP and nitric oxide (which helped explain how nitroglycerine work for heart disease).

Before a student in Dixon Woodbury’s Biophysics class started working on it last fall, Wikipedia’s cyclic guanosine monophosphate article wasn’t in bad shape.

The average reader might have found it challenging and a bit dense, but it seemed to include most of the important parts – sections about the molecule’s biosynthesis, its function, degradation, and its ability to activate protein kinase. It would take someone with some depth of knowledge to recognize some of the gaps in the article, and figure out how to fill them – and the Brigham Young University student was up to the challenge.

The student editor added a section about the discovery of cyclic GMP and the work that won Furchgott, Ignarro and Murad a Nobel Prize. They also added sections detailing cyclic GMP’s role in cardiovascular disease, major depressive disorder, and the way certain pathogens manipulate it to help them evade the immune system.

As they added information and improved the quality of Wikipedia’s cyclic GMP article, the student editor made this knowledge available to a much wider swath of the public (including me).

And that let me solve a mystery that has tugged at the back of my mind for decades – how does nitroglycerine, an explosive, help people with angina? I now know nitroglycerine releases nitric oxide, which triggers the release of cyclic GMP. And that sets in motion a series of steps that cause muscle cells to relax, which relieves their chest pain.

What mystery might your students help solve, just by editing Wikipedia?

Our support for STEM classes like Dixon Woodbury’s is available thanks to the Guru Krupa Foundation.

Interested in incorporating a Wikipedia assignment into your course? Visit teach.wikiedu.org to learn more about the free resources, digital tools, and staff support that Wiki Education offers to postsecondary instructors in the United States and Canada.

I really appreciate how this post connects seemingly unrelated topics like explosives and depression through the lens of cyclic GMP. It’s fascinating to see how second messengers like cyclic GMP bridge external signals and internal cellular responses—something I hadn’t fully appreciated before. It makes me wonder how many other hidden links between biology and medicine are waiting to be uncovered by students digging into the research.