Information about marginalized and minority communities in the United States often goes unmentioned in history books and popular textbooks. Women and non-European communities in particular may be underrepresented, misrepresented, or missing altogether.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Wikipedia follows the historical trend of disproportionately covering biographies of men, with only 16.78% of all biographies on Wikipedia about women. Research suggests two probable causes for this disparity: Wikipedia’s editor base is at least 80% male, so the people writing biographies may not notice the disparity; and Wikipedia is a tertiary reflection of the academy’s literature, so the gender imbalance has deeper roots in the publishing systems that preexist Wikipedia.

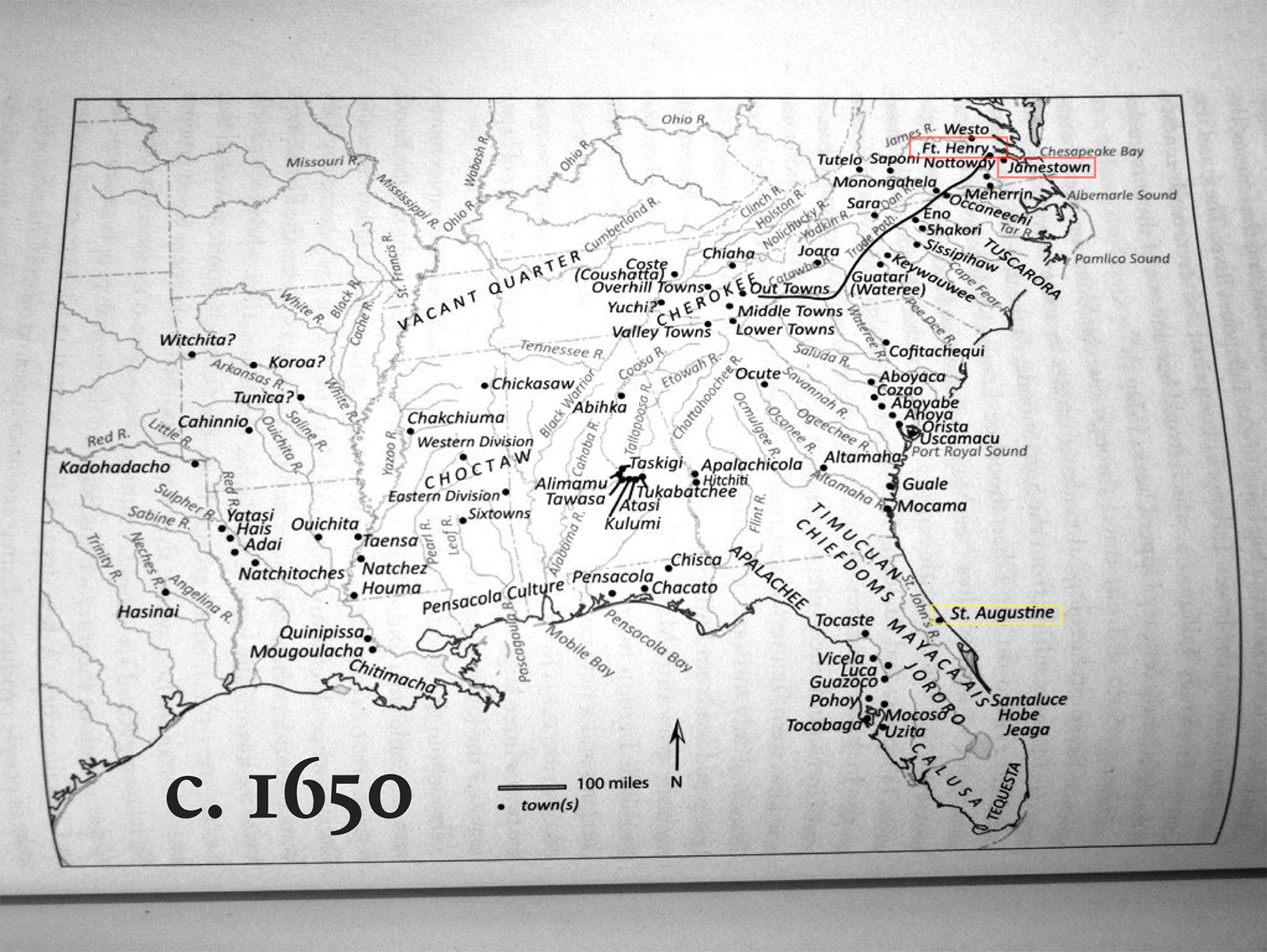

At the recent American Anthropological Association’s annual meeting, Dr. Carwil Bjork-James pointed to the following map as an example of how information becomes skewed in the United States. The map illustrates the southeastern United States around the year 1650.

Dr. Bjork-James presented this map to our workshop audience and said the attendees’ response resembled the one he gets from his students. Most people have not heard of the native settlements listed alongside the familiar ones: St. Augustine, Jamestown, and Fort Henry. What the known entities have in common, of course, is that they’re the colonial settlements that Americans may consider the first “cities” in the future United States. In most maps of that time period that frame our understanding of our nation’s history, the settlements of indigenous peoples are conspicuously absent.

When cartographers create a map, like the one above, they cannot include all available information but must choose items relevant to the purpose of the map. This inherently introduces bias—what do they want the audience to conclude from their depiction? What data points should the mapmaker include? Which ones should they omit?

Let’s say you wanted to create a map related to the Dakota Access Pipeline. If you wanted Americans to support the pipeline’s route through Sioux territory, you may create a map of America’s 72,000 miles of crude oil pipelines, suggesting to readers the Dakota Access Pipeline is “business as usual.” Another cartographer with a different perspective may look at this map and see a glaring omission of data: where have we already experienced pipeline accidents that have endangered the environment and people living near them? A third cartographer may then add rivers and other water sources to the map. Each addition helps readers determine whether the pipeline is a threat to the primary source of drinking water for the Sioux. Providing information on both sides of the issue better equips readers as they develop their own position.

As more mapmakers make changes they deem important, readers develop a more complete picture of the mapped data. This is the power of crowdsourcing. As we get a more complete picture, we become better-equipped to discern fact from fiction and to understand gray areas between the black and white issues often framed in mainstream news outlets.

On Wikipedia, we bring together different people—each with her or his own bias—and we build a repository of knowledge that represents the world as we understand it thus far, not unlike a map. The more diverse life experiences we have building that repository, the more complete and inclusive the information becomes for readers. This gives Wikipedia readers the agency to consider all information and form opinions based on various studies and news reports. We’ve spent 16 years working out a system to achieve consensus among editors. The system isn’t perfect, and neither are the individual editors. But together, as we diversify the editor-base and their innate biases, we create an encyclopedia that better represents the world around us.

This is why Wiki Education’s work is so important—we consistently bring thousands of new voices to Wikipedia every semester. University instructors join our program to assign students to write Wikipedia articles. We provide the training and guidance they need as new users to write high-quality content that educates Wikipedia’s 500 million monthly readers. Students evaluate Wikipedia’s current portrayal of a topic related to their course, review the reliable research and empirical evidence available on the topic, and fill in the content gaps.

Not only that, but our students are 68% women, which in itself is a stark difference from Wikipedia’s well-documented gender gap. Students in women’s studies classrooms are challenging Wikipedia’s content every day and questioning whether it represents the experiences of all people. Then, they use their intersectional lens to write women, gender, and sexuality issues into the encyclopedia, helping readers develop a better-informed map of existing knowledge. As Dr. Lisa Anderson said to me at the National Women’s Studies Association’s conference last month: “This is the feminist work.” Feminist studies and activism center on the belief that inclusivity is empowering and serves institutions to their betterment, and that includes Wikipedia.

The students we work with are developing the media literacy skills it takes to question a 1650 map of the future United States that ignores native settlements, so we’re already doing our community a great service. Add to that the diverse perspectives and knowledge they’re making available to the world, and you have an assignment that belongs in the higher ed classroom. If you agree Wikipedia-writing assignments are a win-win pedagogical tool, here’s how you can support the work we’re doing across the United States and Canada:

- Teach with us: If you’re an instructor at a college or university in the U.S. or Canada, consider incorporating a Wikipedia-writing assignment into your class. Email us at contact@wikiedu.org.

- Spread the word: If you know someone who might be interested in teaching with Wikipedia, encourage them to email us at contact@wikiedu.org.

- Make a donation: As a nonprofit, we rely on generous contributions to scale our impact. Your gift today will help us support more students next year.